When we have a fever, everything tastes bitter and unpleasant, but once we have seen other people taking the same food without revulsion, we stop blaming the food and drink, and start to blame ourselves and our illness. In the same way, we will stop blaming and being disgruntled at circumstances if we see other people cheerfully accepting identical situations without getting upset. So when unwelcome incidents occur, it is also good for contentment not to ignore all the gratifying and nice things we have, but to use a process of blending to make the better aspects of our lives obscure the glare of the worse ones. But what happens at the moment is that, although when our eyes are harmed by excessively brilliant things we look away and soothe them with the colours that flowers and grasses provide, we treat the mind differently: we strain it to glimpse the aspects that hurt it, and we force it to occupy itself with thoughts of the things that irritate it, by tearing it almost violently away from the better aspects. And yet the question addressed to the busybody can be transferred to this context and fit in nicely: 'You spiteful man, why are you so quick to spot someone else's weakness, but overlook your own?' So we might ask: why, my friend, do you obsessively contemplate your own weakness and contantly clarify and revivify it, but fail to apply your mind to the good things you have?

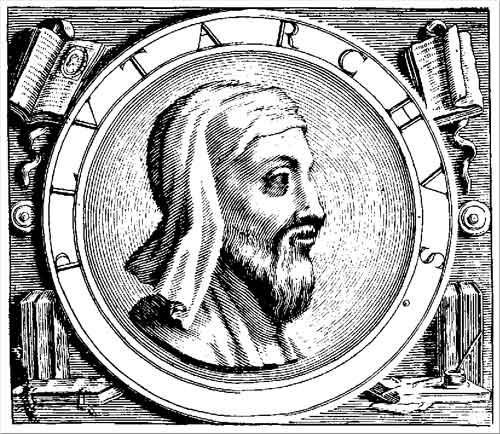

- Plutarch, "On Contentment"

"we will stop blaming and being disgruntled at circumstances if we see other people cheerfully accepting identical situations without getting upset."

ReplyDeleteMaybe sometimes not such a good thing... like the Milgram variant where there are multiple people blithely giving the shocks, bystander effect, Asch experiments... or Nazis. :/

Yeah ... maybe what's good for contentment isn't always good for morality?

ReplyDelete